Humanity Calendar

What We Discover

Group Portfolio.

Gender, Race, and Immigration in Historical and Contemporary Nurse Training

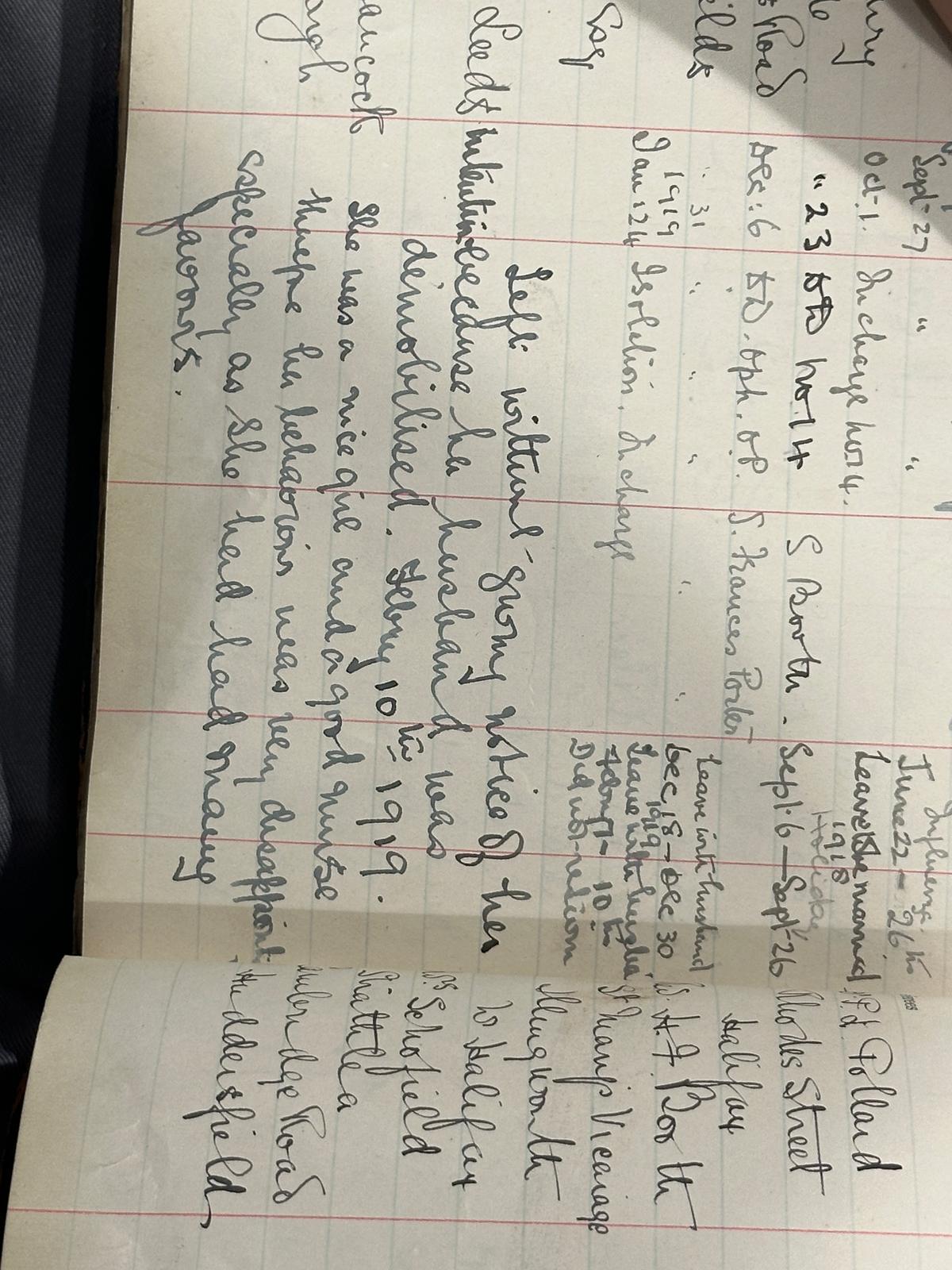

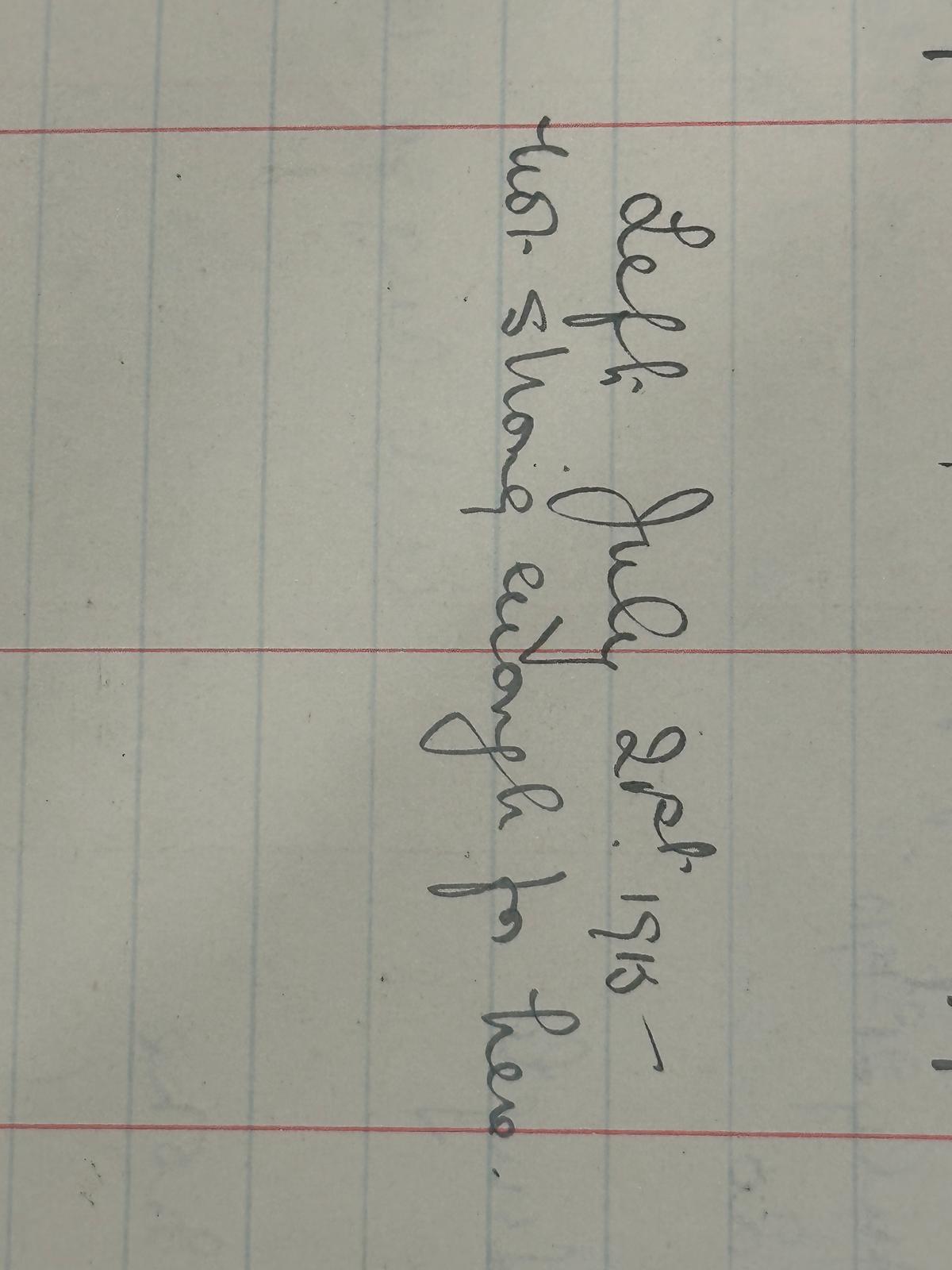

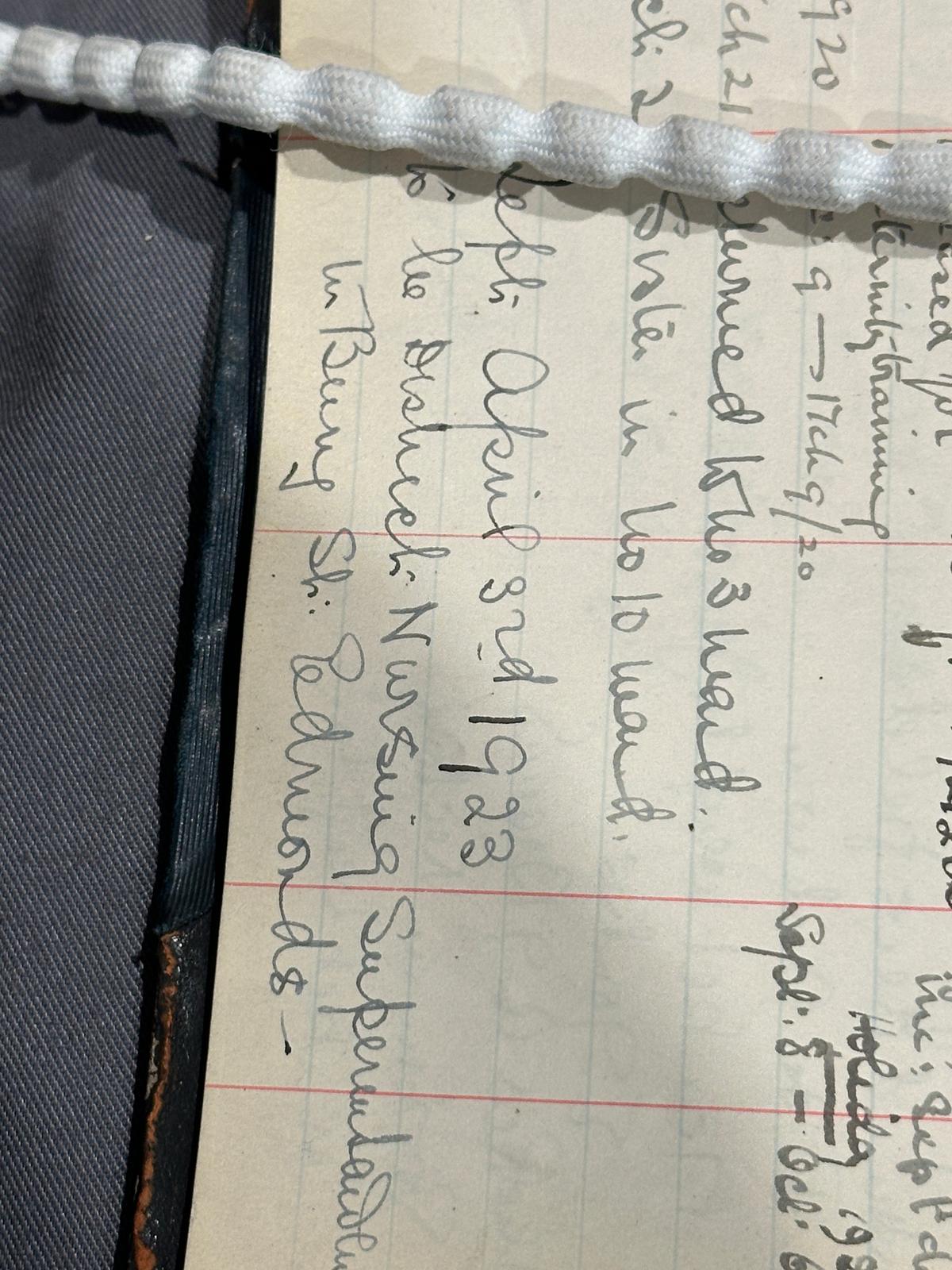

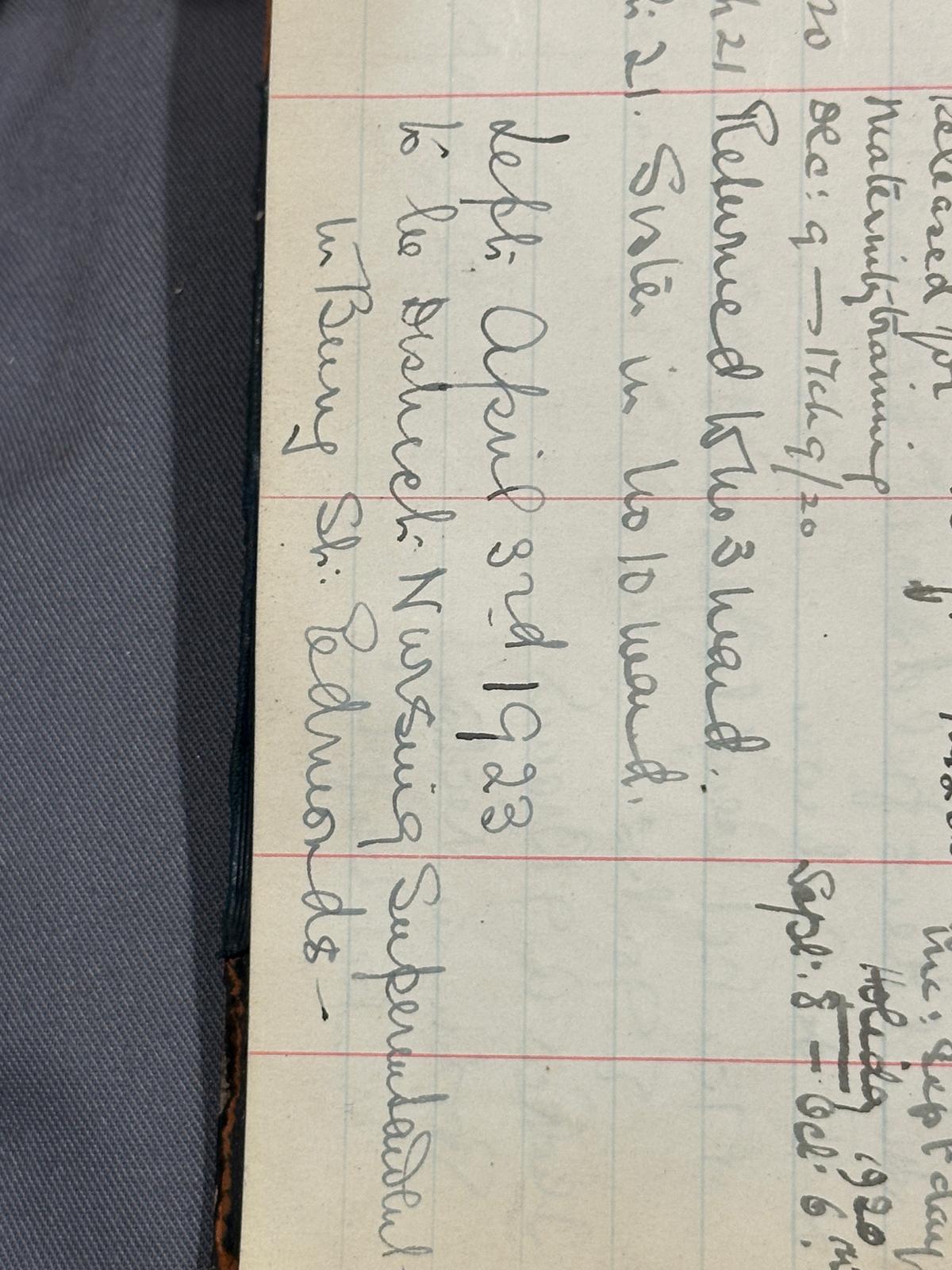

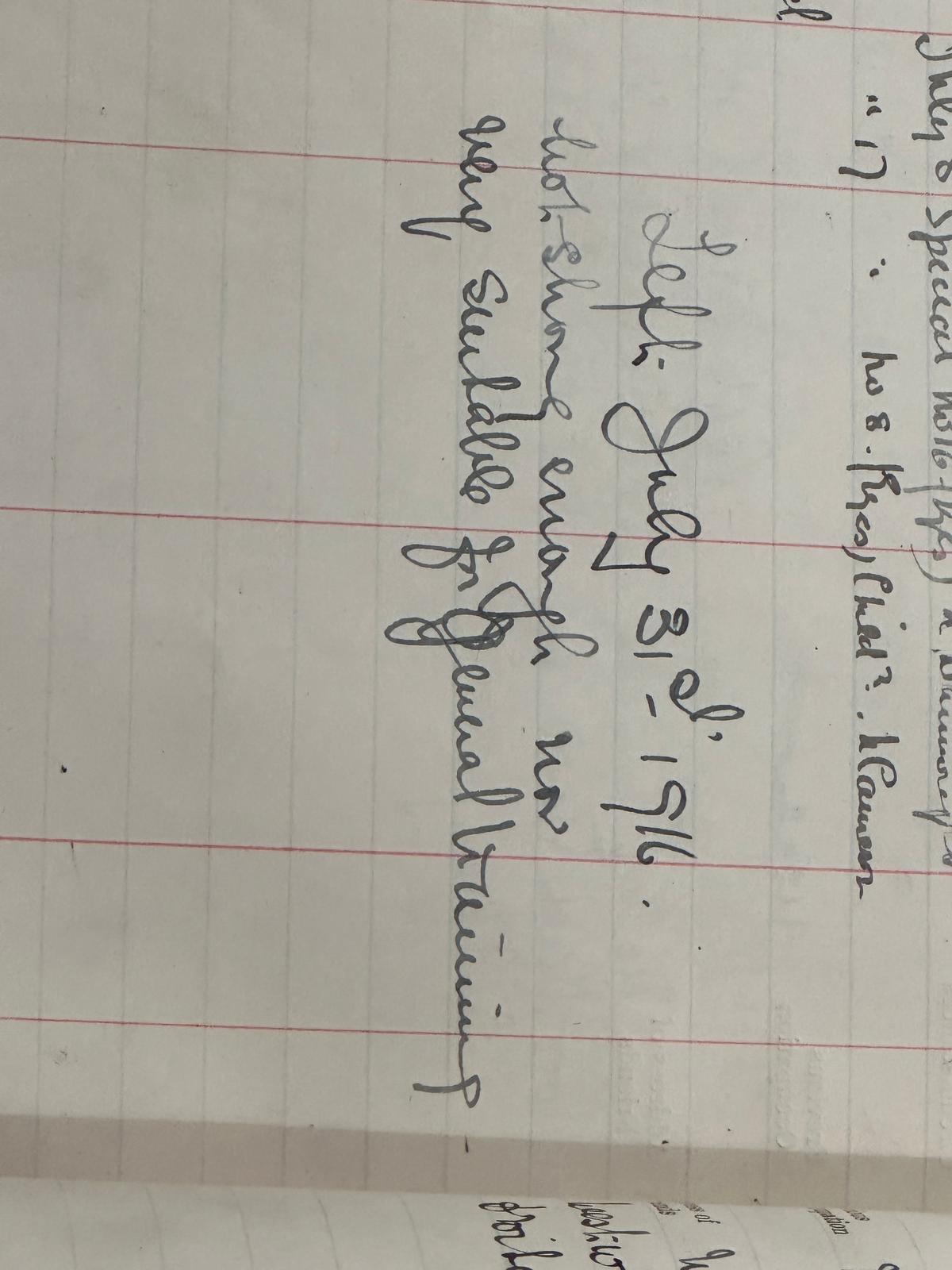

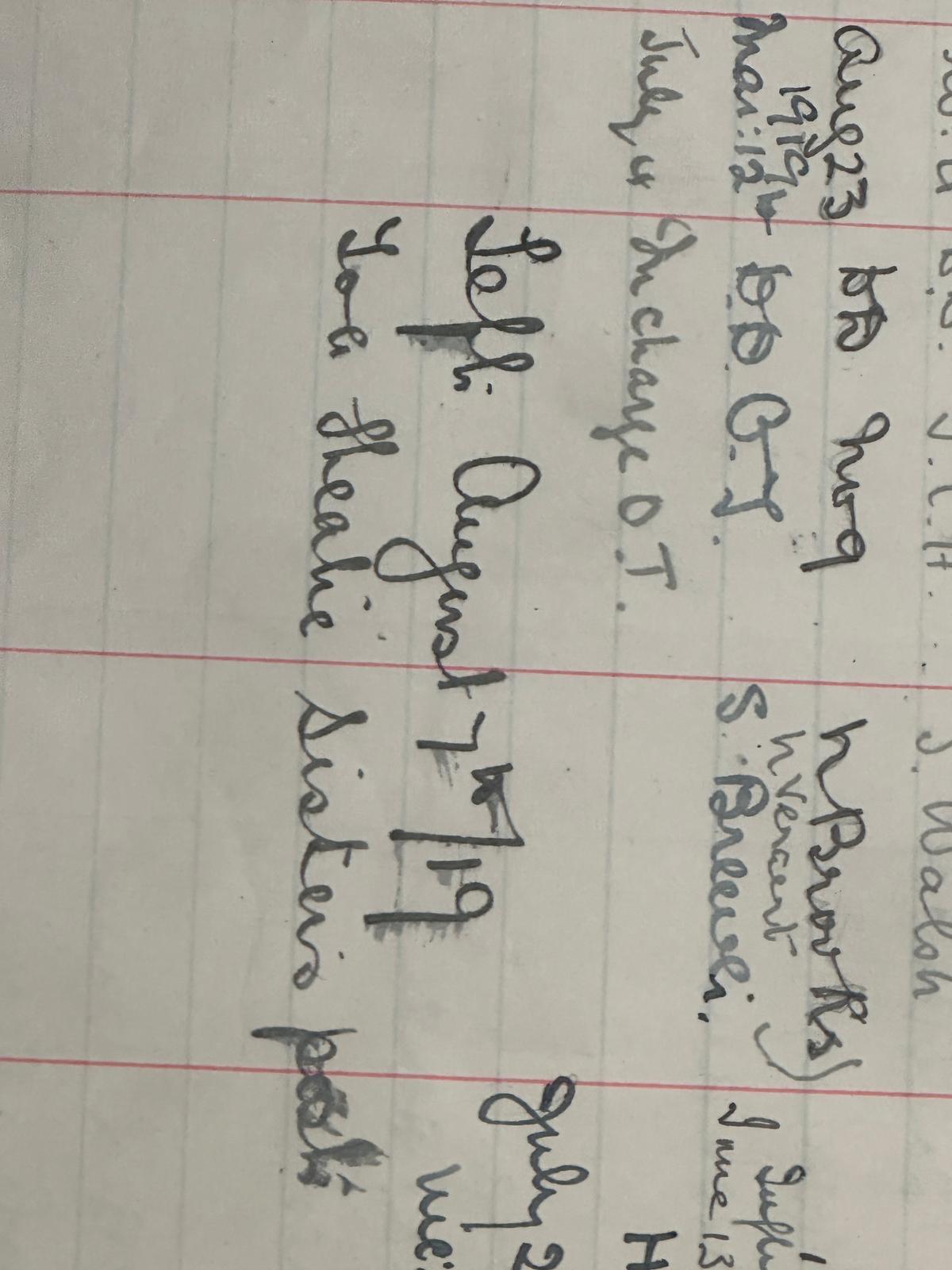

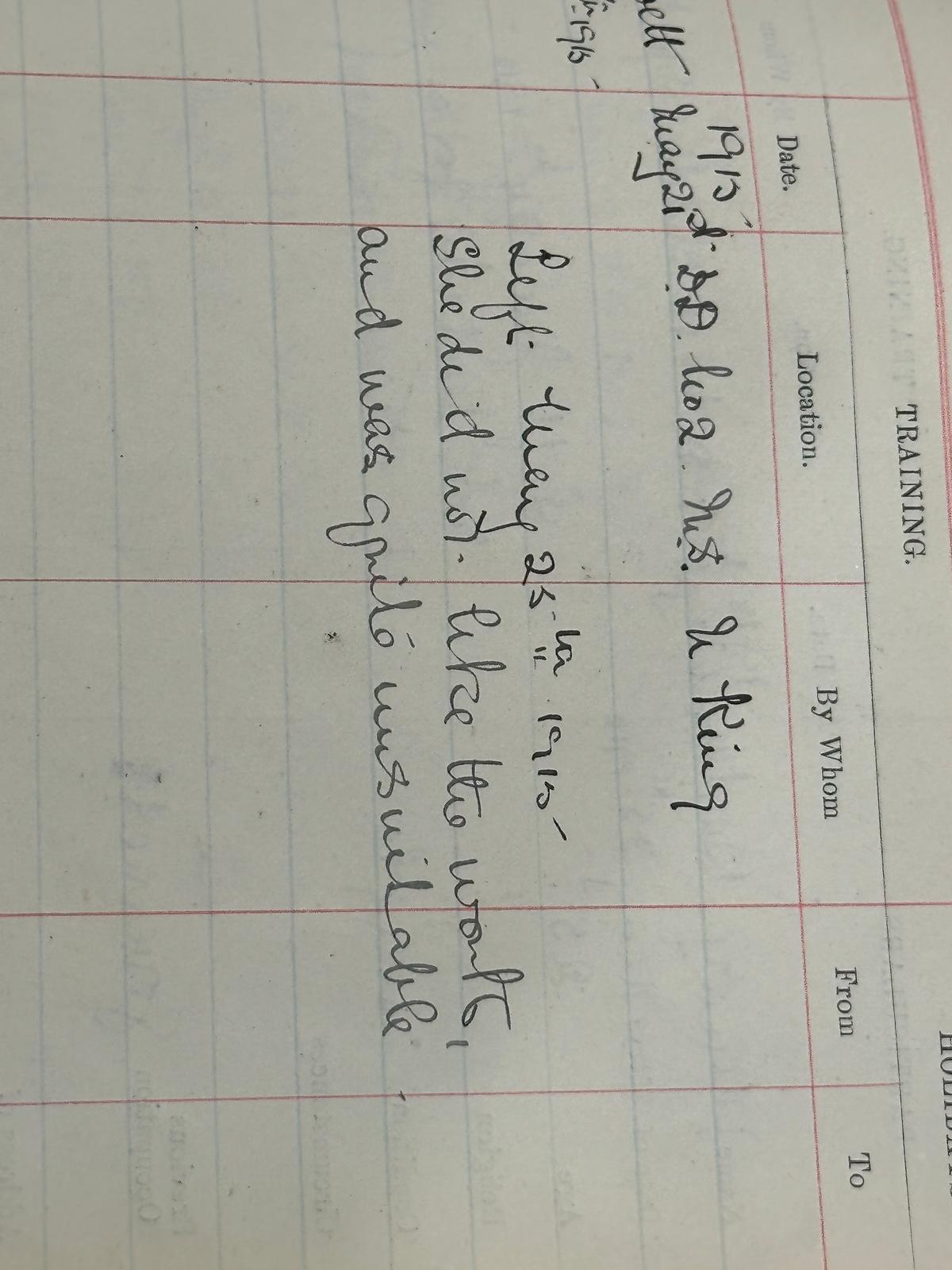

White British women formed the majority of the nursing workforce in early 20th-century Britain, which was a gendered and classed profession. A structural silence about racial diversity is suggested by the fact that archival registers from organizations such as St Mary's Hospital (1921–1932) record nursing trainees by age, marital status, and length of training, but leave out information on nationality or race (The Guardian, 2024). This exclusion functioned to center whiteness and femininity as normative categories within the profession.

According to academics, these early bureaucratic framings created a gender- and racially exclusive professional identity (Evans, 2004). The feminization of nursing reinforced conventional caregiving responsibilities associated with moral obligation, even as it expanded career opportunities for women (Davies, 1995). Crucially, this foundation set the stage for gendered assumptions that continue to shape nursing's current structure and perception.

Contemporary data from NHS Providers (2024) shows that 77% of nursing staff are women, continuing the profession’s historical feminization. However, sociologist Williams (1992) identifies a paradox known as the “glass escalator,” wherein men in feminized professions benefit from accelerated promotion and better pay.

Gender Pay Gap Service (2024) data reports a mean wage gap of 20.7% and a median gap of 9.5% in the healthcare sector, with women receiving significantly fewer bonuses. Despite numerical dominance, female nurses continue to face systemic pay inequity and slower career advancement, reflecting the persistence of gendered barriers originally institutionalized in the early 20th century.

The NHS workforce has become significantly more ethnically and nationally diverse. By 2024, 25% of staff identified as from minority ethnic backgrounds, and over 20% were non-UK nationals (NHS Digital, 2024). This shift marks a stark departure from the near-total whiteness recorded in early nurse registers.

Recruitment from countries such as India and the Philippines has been a deliberate NHS strategy to address staffing shortages (Commons Library, 2024). Yet, diversity in numbers has not equated to equity in outcomes. NHS England (2018) reports that Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) staff are less likely to be promoted and more likely to face discrimination. White applicants remain 1.45 times more likely to be recruited than BME candidates. These findings echo Ahmed’s (2012) critique of institutional diversity rhetoric that masks enduring racialized hierarchies.

This study employed digital tools—including Optical Character Recognition (OCR), data visualization platforms like Flourish, and GIS mapping—to analyse archival training registers and contemporary NHS datasets. These methods revealed patterns of exclusion in historical records and demographic shifts in current workforce composition.

Visualizations (see Appendix) map changes in nurse origins, showing a dramatic rise in global mobility and ethnic diversity. Comparative timelines illustrate how immigration policies, such as post-war Commonwealth recruitment drives, have shaped workforce demographics. These tools enable a more nuanced understanding of continuity, disruption, and institutional memory within the nursing profession.

This assessment involved collaboration with archivists from the British Library and peer researchers in a digital methods workshop. Group discussions guided the ethical handling of sensitive demographic data and the contextual interpretation of historical gaps. This iterative and dialogic process shaped the analytical lens applied in this review, fostering interdisciplinary engagement and methodological reflexivity. Through collaborative analysis sessions, the team was able to critically examine how archival silences are produced and how digital tools can both reveal and obscure patterns. These reflections informed key decisions about framing, sourcing, and presenting historical and contemporary narratives within the review.

Conclusion: Learning from the Past to Inform the Future

This literature review demonstrates that structural inequalities in nurse training—rooted in gendered and racialized histories—continue to shape contemporary experiences. While the NHS has diversified, inclusion alone is not equity. The combination of archival analysis, digital tools, and critical theory provides a robust framework for understanding how legacies of exclusion persist beneath surface-level change. Digital archives not only recover hidden histories but also compel institutions to account for them. Genuine inclusivity in nursing requires both historical reckoning and systemic transformation.

References (Leeds Harvard Style)

Ahmed, S., 2012. On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Commons Library, 2024. International recruitment in the NHS. [online] Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7783/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Davies, C., 1995. Gender and the professional predicament in nursing. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Evans, T., 2004. Professionals and patriarchy: The gendered politics of nurse training. Sociological Review, 52(1), pp.55–74.

Gender Pay Gap Service, 2024. Healthcare sector pay gap report. [online] Available at: https://gender-pay-gap.service.gov.uk [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

NHS Digital, 2024. Workforce statistics. [online] Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

NHS England, 2018. Workforce Race Equality Standard: 2018 data analysis report for NHS Trusts. [online] Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/wres-2018-report-v1.pdf [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

NHS Providers, 2024. State of the provider sector report. [online] Available at: https://nhsproviders.org [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

The Guardian, 2024. Whiteness of the ward: Hidden histories in British nursing. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Williams, C.L., 1992. The glass escalator: Hidden advantages for men in the “female” professions. Social Problems, 39(3), pp.253–267.